Where can you go for immoral instruction? You can find plenty of pontification about Victorian morals, but the street-smart facts about amorality rarely come through book learning. Fortunately, we have The Right Way to Do Wrong, “Yellow Kid” Weil: The Autobiography of America’s Master Swindler and You Can’t Win to show us how to be bad.

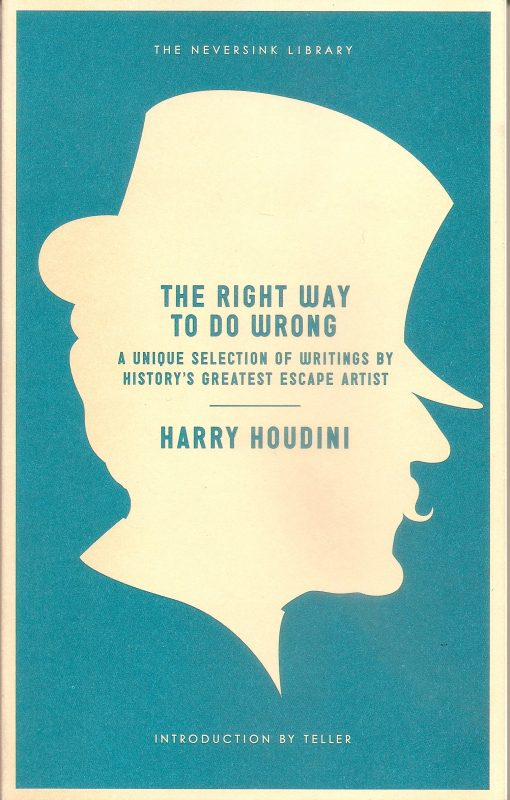

Master magician Harry Houdini spent some time in prisons, but not as a criminal. As “The Great Self-Liberator, World’s Handcuff King, and Prison-Breaker,” the escape artist freed himself from jail cells. He also befriended police and turnkeys, and was able to interview criminals.

The Right Way to Do Wrong (Melville House, 2012) collects essays by Houdini on the tricks of the criminal trade that he gleaned from the inmates. He outlines how much a criminal can expect to earn, how to plan a burglary, how to pickpocket and how to scam via bunco games, fakes and hoaxes. Some of the essays waft with the odor of baloney sausage and other BS. Instead of citing sources, he will say, “A London burglar, who served a long sentence, told the chaplain of the prison the following amusing story of one of his experiences,” or “Among the clever coups that have come to my attention here is one related by an ex-convict, and published recently in an English periodical that presents some rather interesting features.” Despite tips like planning a burglary by walking backward, Houdini admonishes, ‘[I] t can be said that IT DOES NOT PAY TO LEAD A DISHONEST LIFE, and those who read this book, although it will inform them “The Right Way to Do Wrong,” all I have to say is one word and that is “DON’T.”’

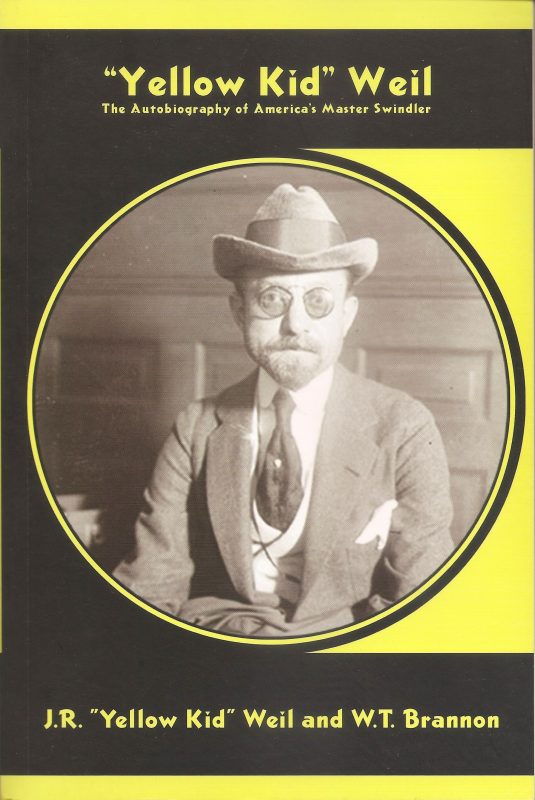

In “Yellow Kid” Weil: The Autobiography of America’s Master Swindler (Nabat/AK Press, 2011), the con artist justifies his schemes. “I have never taken a dime from honest, hard-working people who could not afford to lose. But the victims of confidence games are usually people who are wealthy and can afford to pay the con man’s price for the lesson.”

Contradicting his own justification, the native Chicagoan began by swindling yokels as a plant in the crowd for Doc Meriwether and his miracle elixir (rainwater, cascara and alcohol). Weil’s chicanery grew more elaborate. He printed fake property deeds, extended credit through fake banks and sold nonexistent stocks to the wealthy and greedy. His ill-gotten gains were estimated at $8,000,000. When the cash was available, it went to a lavish lifestyle. He played the horses. He owned a yacht and imported automobiles. Both required maintenance bills. Ironically, his greatest losses were through legitimate business dealings. He invested $25,000 in the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus show, only to see a rainy season drive the audiences away. He also had half a million in Chicago real estate investments that had to be sold at a loss. Here’s to honest work!

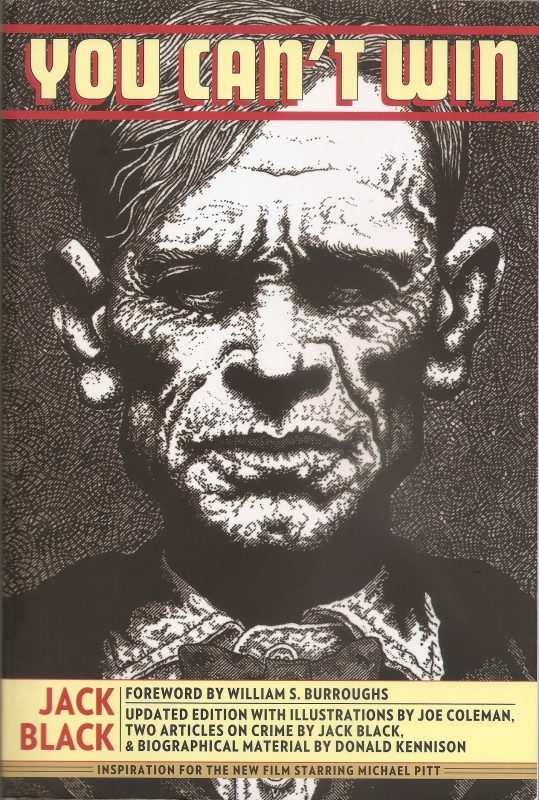

In the foreword to Jack Black’s You Can’t Win (Feral House, 2013), William S. Burroughs captures the tone of Black’s life story. ‘I was fascinated by this glimpse of an underworld of seedy rooming-houses, pool parlors, cat houses and opium dens, of bull pens and cat burglars and hobo jungles. I learned about the Johnson Family of good bums and thieves, with a code of conduct that made more sense to me than the arbitrary, hypocritical rules that were taken for granted as being “right” by my peers.’

Jack Black’s criminal career begins in his youth, working in a cigar store that served as a front for back room gambling. His disreputable associates lead him to burglary. He rides the rails with hobos (whose revelries often end in murder), learns how to dress down and keep his head down after escaping from prisons, blows up safes, and demonstrates the necessity of holding a gun in one hand while the other slips under a pillow to reach a wallet. He admits, “When I first began stealing I had but a dim realization of its wrong. I accepted it as the thing to do because it was done by the people I was with; besides, it was adventurous and thrilling. Later it became an everyday, cold-blooded business.” The social contract of the criminal life remains strong. In his essay A Burglar Looks at Laws and Codes, Black muses, “The more strictly a criminal adheres to the underworld code the greater will be his handicap if, and when, he decides to mend his ways. This adherence makes him friends, and he is proud of it; but these very friends help to anchor him in that life. The upperworld does not realize how great a part this plays in the lapses of offenders who are given an opportunity to reform.”

The three books point out the action and adventure that come with being bad, but also the consequences. Crime pays, but it comes with a price.

There are no voices yet... Post-script us a message below, won't you?