“Experience is simply the name we give our mistakes.” –Oscar Wilde

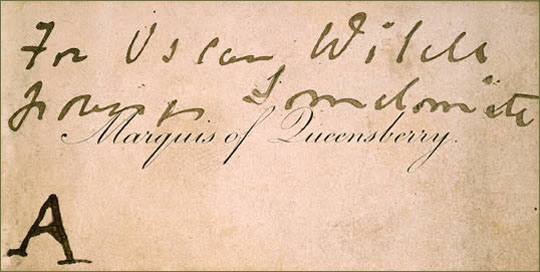

On February 18, 1895, Lord John Douglas the Marquis of Queensbury left his business card at the Albemarle Club for Oscar Wilde, who was his son’s lover. A note on the card read, “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic].” The literary figure countered with a libel suit. This turned out to be a very bad idea.

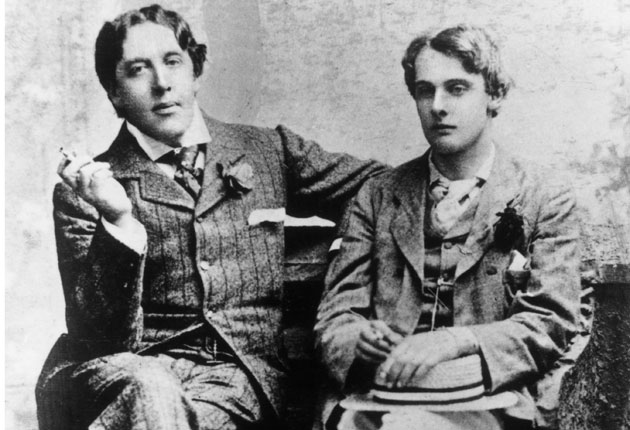

Wilde met Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas in the summer of 1891. The Oxford undergraduate Bosie was a fan, having read The Picture of Dorian Gray several times. They became lovers. Bosie introduced Wilde to the Victorian underbelly of male prostitution. The author wined and dined young men for hire and sealed the deal in a hotel room. He pampered the prostitutes and Bosie with gifts. In the essay De Profundis, Wilde reflected on the experience, “”It was like feasting with panthers; the danger was half the excitement… I did not know that when they were to strike at me it was to be at another’s piping and at another’s pay.” When they met in 1891, Wilde was 36 and Bosie was 20.

The Marquis of Queensbury did not approve. He was a boxing aficionado who sponsored the Queensbury rules that shaped the sport. In June 1894, he threatened Wilde. “[I]f I catch you and my son again in any public restaurant I will thrash you.” Wilde riposted, “I don’t know what the Queensberry rules are, but the Oscar Wilde rule is to shoot on sight.” This surely incensed the Marquis. His oldest son, Francis Douglas the Viscount Drumlanrig, died tragically that year. Officially, Francis was killed in a shooting accident, but there were stories that he shot himself over an affair with Prime Minister Archibald Primrose the Earl of Rosebery. The father made it known that he had contempt for “Snob Queers like Roseberry [sic].”

Queensbury dropped off his card at the Albemarle and Wilde received it on February 28, 1895. With Bosie’s support, Wilde had the father arrested for criminal libel. The trial began on April 3.

Under the Libel Act of 1843, Queensbury could be convicted for up to two years if his public declaration that Wilde was a “somdomite” were proven false. Libel is a published defamation of character. In this case, it was the calling card. Sodomy, in the Victorian era, could be seen as any sex that was not straightforward man-woman penis-vagina. Queensbury and his lawyer Edward Carson used private detectives to find Wilde’s male escorts.

Carson found them. He presented the working class rent boys at the trial as Wilde’s sexual partners. Wilde admitted that he knew them and they were friends, despite the social barriers. Carson grilled Wilde on whether or not he kissed a particular servant. “Oh, dear no,” Wilde replied with his typical wit. “He was a particularly plain boy – unfortunately ugly – I pitied him for it.” Wit did not win the case. After the several prostitutes testified in court to having sex with him, Wilde dropped the case. Queensbury was acquitted. The Libel Act forced Wilde to pay the court costs for a false accusation, which bankrupted him.

Furthermore, Wilde’s liaisons led to his arrest for “gross indecency.” This trial began on April 26, 1895. He was convicted, sentenced and imprisoned on May 25, 1985. He was not released until May 18, 1897.

Wilde may have had an enduring wit that provided him with fame and acclaim, but he neglected his own words, “He knew the precise psychological moment when to say nothing.”

There are no voices yet... Post-script us a message below, won't you?